Dylan Thomas and “The Boy with a Note”

Dylan Thomas and “The Boy with a Note”

It is a timely reminder of ones own mortality when you suddenly find yourself older than one of your heroes. I am now older than Woody Guthrie was when he died, Peter Sellers and also James Dean probably Blind Blake definitely Jimi Hendrix and Dylan Thomas. Dylan died in New York on 9th November 1953 aged 39 years.

It was the realization of how young Dylan was, when the deadly cocktail of morphine and booze combined with his suspected diabetes sent him into the coma from which he never regained consciousness, that began my thoughts about writing something.

It is my belief that it was not just the chemicals that killed Dylan. His lack of strength to walk away from the dilemmas of morality and his way of dealing with his guilt simply exhausted him. The fight was knocked out of him. It was all too much, he threw in the towel.

With hindsight the most earth shattering problems often pale into insignificance, and yesterday’s intensities seem trivial. People don’t always forget but they do forgive and vice versa.

Poor young Dylan worked himself into a hole that many men with less sensitivity are able to climb out of, walk away from, or put behind them. Somehow I think his middle class chapel upbringing held him in his “chains “ of guilt and actively contributed to his demise. He was able to break the little rules but the big ones he would never be free.

Once I had the privilege of chatting to Sir John Betjeman on my fairly simple grasp of poetry and the subject of rules in poetic structure and Sir John said

“Of course one must have rules in order to break them”

Dylan did not so much break rules but he did break the petty conventions and constraints he was born into. By many of todays standards his behaviour was not that bad but you get the sense that he delighted in snapping the threads that bound him to his class, rather like a little boy blowing raspberries in church.

His principle sufferings were with his guilt not his hangovers. By any standards he was not a heavy drinker and seldom drank spirits. I am willing to bet that his “eighteen straight whiskies” claim was a lie. I certainly know people who have survived more! Drink however oiled the locks on his prison door and enabled him to wittily or whimperingly pick his way out of the cell.

By all accounts he was a wonderful raconteur and it is easy to imagine the young man holding fellow arty types in thrall, glass in hand, standing in some Fitzrovian pub, taking the mickey or delivering witty barbs or telling dirty jokes, absolutely revelling in the boozey freedom some way away from Cwmdonkin Drive in Swansea.

Drink enabled him to be simply naughty and rude at first, and only later to require the same medicine to repair the pain both mental and physical, of what the indulgences of the night before had caused.

On reading the Constantine Fitzgibbon book about Dylan I found myself constantly imploring him in my mind

“Get a grip of yourself!

It will be all right.

Just get to your forties and you will make it to your fifties and from thence to whatever. It is survivable.”

The sort of thing you can only say when you have lived for ten years longer than your hero subject. Whilst knowing that your own art will always remain in the shadow of theirs, you are nevertheless enabled to offer an opinion on life and art based solely on the extra years by which you have survived them.

Dylan came from a time that it was fashionable for artists to appear to be on death’s door. It indicated an abstraction from the world and taking care of oneself, living only for the muse and a fleeting chance to grab at inspiration and turn it into something tangible and beautiful. His affected wracking cough only produced satisfaction when he was able to produce a tiny speck of blood in his handkerchief. This was to infer that he was suffering from the dreaded TB or some other disease indicative of deprivation. His real disablement was self-inflicted injury through hangovers and accidents causing him to break his “chicken bones” as Caitlin (his wife) called them. His unknown illness may have been diabetes it is now conjectured.

My other empathising with him came from his solo performance work and a glimpse of what the adulation he received must have done to him, especially in America, which is where he hoped principally to earn his fortune.

Bound by pre rock and roll conventions of politeness and etiquette, it would have meant him having to be civil to his hosts no matter how banal they may have appeared to him, or how bad his guilt or hangover might have been.

Randy Newman once described foreign touring as “shaking hands with thousands of teeth”. I am sure Dylan often found it hard to show his own without gritting them, and of course there was no one to blame for his condition but himself, and he would have known this.

It does not get any harder.

I recalled my own early days in the USA and the warmth and the friendliness of the people who speak the same language but nevertheless regard you as some sort of non-threatening alien on whose every word they hang. You adapt your humour and pronunciation and yet they will still tell you how they “love the way you talk” and the sound you make.

They must have adored Dylan for his mighty renditions of his poetry alone. His ready and quick wit, and his rakish naughtiness and ribaldry must have only added to his exoticness and risk taking.

They must have adored Dylan for his mighty renditions of his poetry alone. His ready and quick wit, and his rakish naughtiness and ribaldry must have only added to his exoticness and risk taking.

Dylan must have relished all this at first but his inability to manage his “affaires” (both senses) must have caused irritation on top of all the other burdens he was carrying. Those darkest hours before the dawn and a very long way from home.

Poor Caitlin, a true bohemian, with her highly dysfunctional upbringing trying to bring up a family on “wishes and dreams”. Constantly reminding Dylan of her own artistic sacrifices and the need for money for essentials whist he was being feted and admired in America. Her sense of outrage at the hospital where Dylan died is wholly understandable. Not only was she grief stricken, she was demented by the fact that he could have gone without honouring the commitment to her and the children.

This was not supposed to happen. They say those the Gods love die young. However nothing convinces me that the gods wanted Dylan. I think they took their eye off the ball. He might have been only thirty-nine when he died but in all other aspects he had accumulated a full three score and ten year burden. Caitlin became totally unhinged temporarily and her account in her book “Left Over Life to Kill” is harrowing. Even though she recovered and lived happily for many years afterward with her Italian husband Guiseppe and new son in Italy, when she died some forty years after Dylan, she was buried with him in the graveyard in Laugharne, in accordance with her wishes.

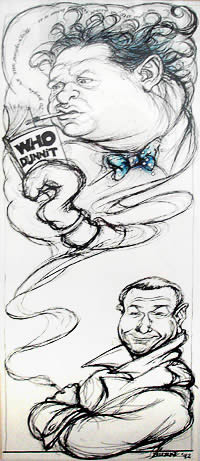

In her memoirs, Caitlin revealed that Dylan loved the raciness of detective fiction and Daniel Farson describes how Dylan “borrowed” a magazine he was carrying for the flight to the States on the one occasion they met. It contained a short story by Raymond Chandler.

Here was my entry into Dylan’s world. I would be a “gum shoe” detective and follow Dylan, slipping in and out of doorways and writing notes to be delivered at the never-ending inquest to his life and death. Armed with this device I could go anywhere and not be seen whilst I accumulated the evidence.

I began by attempting to illustrate the character of the man from the image of the fat boy in class wriggling out of games lessons with a forged note from his “Mam”. (In fact the young Dylan once won a race in school and carried the local newspaper report with him for many years.) But “begging to be excused” was central to the work. Starting with begging to be excused games he begs to excused fame, blame, and shame at various times in the narrative.

In the John Wayne school of manliness, a man never apologises, it is viewed as a sign of weakness and so it only compounds Dylan’s wretchedness by needing this constant mum’s understanding and non catholic absolution through art, in order that he can continue on his way.

In the John Wayne school of manliness, a man never apologises, it is viewed as a sign of weakness and so it only compounds Dylan’s wretchedness by needing this constant mum’s understanding and non catholic absolution through art, in order that he can continue on his way.

I think fame corrupted him. All he really sought was recognition and some small reward for his beautiful work. In spite of what he sometimes said, I do really think he was at his happiest in Wales. Probably in the bar at Browns Hotel in Laugharne, discussing the village business in a parochial way with his friends the Williamses. This I feel is reflected in his most famous work “Under Milk Wood” At the time of writing my piece I had not seen or read that work. For me it is with his wonderful skill with words that I am moved.

“It was my twentieth year to heaven”

Or

“In the mercy of his means

Or

The force with which the green fuse drives the flower

Or

I sang in my chains like the sea

Or…or… or…..

I am sure all the poems have deep significance for Dylan in spite of his reluctance to discuss or analyse them. I am equally sure he was prepared to sacrifice exact expression of meaning for the delight of running words together. When asked to explain or describe how to get more meaning from his work he often replied “Love the words” and so I do.

The songwriter’s craft is different to Dylan’s “sullen art” but every now and then, I arrive at a word construction or a particular chord voicing that gives me an inward smile and although I know there are no comparisons to be made with the high art of Poetry, the buzz of getting something “right” is the same in all creative processes. The first time I saw one of his work sheets I was astounded that he listed all potential rhyming words down the side of the page, as do I.

Often to accommodate the rhyme you have to alter the meaning slightly and this in turn can change the tone of the piece. In this building block approach the final satisfaction is wonderful and I often think of him “Booming” triumphantly (Caitlin’s word for Dylan’s reading) out his poems from the little boathouse where he did much of his writing in Laugharne.

Because I chose to write a narrative in poetic form, lines emerged that would not have otherwise have occurred. Hence “dreaming of long limbed summer girls” became the song “Summer Girls” and “Slip-Shod Tap Room Dance” arrived for the same reasons.

I loved the work and as the songs came together I could hardly wait to show somebody what was happening. My early demos were sent to the BBC and Frances Line the then head of radio 2 commissioned it for a production for broadcast. My friend Graham Preskett arranged all the orchestral parts and my early collaborations with Maartin Allcock were the basis for the final work. Another great friend Nerys Hughes read the poem “No Grown Man’s Land” I had written and the wonderful Bob Kingdom read “A Certain Tide” which was supposed to be Dylan’s solo ruminations about a poem he might write. The late Michael Elphick was my detective and read the narrative. I had hoped that I would be able to release the finished work as a CD but for contractual reasons we had to re record the whole thing again. This took place at Woodworm Studios in Oxfordshire and Graham faithfully duplicated all his parts again against out original demos from Raezor studios. This time I read the detective part and found that the poem sounds different when read aloud than it does off the page. Nerys and Bob allowed me to use their original readings, and I was glad to have the extra time to make small adjustments to the earlier piece.

I loved my involvement in this whole work and was sort of sorry when it ended.

Since the original recording I have performed the work in part or whole at the Dylan Thomas Centre in Swansea and read some of Dylan’s own work at a celebration at the Chelsea Hotel in New York.

In 2003, on the 50th anniversary of his death, I played the whole thing for BBC radio Ulster.

Several of the songs from this album have become regularly featured in my live shows and I am bemused by how much this man’s work and life has entered and enhanced my own.

Since that first Fitzgibbon biography I have read all available memoirs, his poems short stories and of course seen several versions of Under Milkwood. I have no wish to change any of the writing of “The Boy with the Note” and I remain, touched by his frailty, moved by his guilt and insecurity, reassured by his self-doubt and totally in awe of his genius.

Credits

Narration: Nerys Hughes, Bob Kingdom, Maggie Reilley & Ralph McTell

Orchestral Arrangements: Graham Preskett

Piano, Guitar & Vocals: Ralph McTell

Bass, Lead Guitar, Keyboards: Maartin Allcock

Saxophone: Andy Findon

Piano & Violin: Graham Preskett

Availability

The Boy With a Note is available to purchase online.